Component Oriented Thinking for Product Managers

How to embed the benefits of components into your product process

What’s a component?

Components mean many things to different members of a modern product team.

For a product manager, using components means building reusable pieces of value which cut down future development time and leads to shipping more value faster.

For a product designer, using components means less time spent arduously repeating the same pattern over and over again in Sketch or Figma files.

For an engineer, using components means building reusable, flexible bits of code.

Whichever perspective you come from, most team members in a cross functional squad will agree that shifting towards a component-oriented mindset is a positive thing. Why?

The benefits of component oriented thinking

Components make everyone’s life a little easier. Here are some of the ways component-oriented thinking can help your team:

Speed

There may well be a steep speed tax to pay initially, but over the long run, a well established set of component libraries will likely help to speed up the development of future releases since you’ll be able to use pre-existing patterns.

User experience

We’ve all had the experience of using a product which has 35 different versions of the same thing.

A dropdown styled in 4 different ways on a settings page.

A button with rounded edges and drop shadow during the onboarding experience and the same button with sharp edges and no drop shadow elsewhere.

Inconsistent designs across the same inputs creates a hideous overall experience which confuses users. It is the opposite of crafting a delightful user experience.

Tech debt

When developers build 23 versions of the same thing, it’s usually one of 2 things driving the decision to do so: 1) the designer hasn’t thought deeply about whether the solution could re-purpose existing components or 2) the engineer couldn’t be bothered to check whether existing components exist which could be repurposed. Using components properly helps reduce the risk of adding tech debt.

Sounds good, but to truly get the benefits of using components requires everyone in your team to think in components. What are the practical ways to embed component-oriented thinking in your team? Let’s have a look.

Practical ways to create a component oriented product team

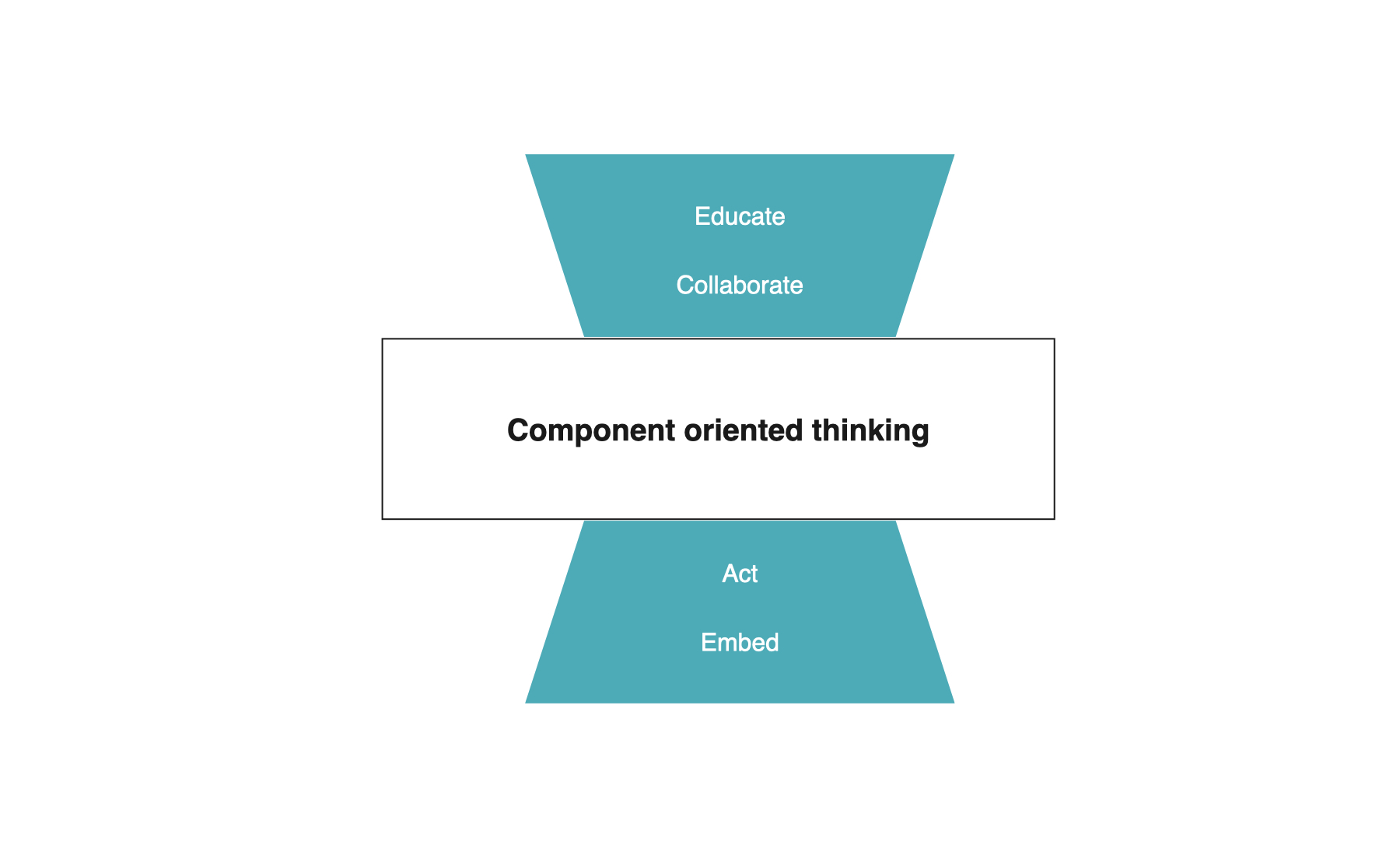

For me, the task of embedding component-oriented thinking into a product team falls into 4 distinct phases:

- Educate

- Collaborate

- Act

- Embed

Yes, I know these sound a little like communist-inspired government guidelines, but bear with me and I’ll explain a bit about each of them.

1. Educate

Part of the problem with working in components, as we previously mentioned, is that they mean different things to different members of a product team. Before your team can successfully adopt a component-oriented mindset, they need to understand what exactly components are.

During the education phase, it’s important that product designers, product managers and developers all understand what components mean in the context of each discipline.

- What exactly is a react component?

- What does a component look like in Sketch or Figma?

- How does building something once and repurposing it elsewhere help with our development process?

These are all important questions to address. Host a component-oriented workshop, invite people who know the answers to such questions to share them. That’s a starting point in your team’s journey towards becoming a component oriented machine.

2. Collaborate

The collaboration phase is designed to take people’s knowledge of components a little deeper by helping members of the team work better together. Developers and designers can sit and work closely together to get a deeper understanding of how components work.

They might even pair ‘program’ together, so that designers appreciate the complexity involved in taking a design and building into a component and engineers appreciate the thinking process which goes into coming up with a solution.

Some suggestions for what can be agreed between developers and designers during this phase include:

- Breakpoints – which breakpoints are we optimising for? Why?

- What % of our product is already built in components today?

- How does a component move from Zeplin or Figma into the engineering cycle?

An exercise in demonstrating the value of components

If you’re struggling to bring the value of shared components to life, one exercise to do to get designers and developers on board with component-oriented thinking is to pick a page or a journey from your product and conduct a component audit.

Pick a screen, or a few screens from an important user journey, print out on an A3 piece of paper and use post it notes to illustrate which parts of the page are currently using shared components. Your goal is to start to build a shared understanding of how much of your product is currently using components today which will help you to identify component debt.

What’s component debt, exactly?

Component debt is measured by the number of times the same task is served by different solutions that could be componentized. Examples could include choosing from a dropdown, filtering a list in a table, searching for something. If there are multiple designs or experiences built which ultimately achieve the same outcome, this contributes to your component tech debt.

At the end of the collaborate stage your designers and developers should have a much better understanding of which parts of your product currently use components and which parts don’t.

Product managers can work closely with designers and developers to assess the level of component debt and decide which bits to prioritise accordingly.

3. Act

Once you’re happy that the team fully understands what % of your product is currently componentized, work closely with your product designers to decide which parts of your product should be componentized first.

There is no hard and fast rule here but it’s sensible to consider:

- Which journeys are the most important to us?

- Which duplicate components are causing the most confusion for users?

- Which duplicate components are causing most problems for the design and engineering process?

Approaches to creating component libraries

A sensible way to approach this is to think of it in a similar way as to how you might tackle tech debt.

Prioritise what you think is important. Build a shared repository of components which can be accessed by both designers and developers and allocate a set amount of time to it.

Don’t try to do it all at once. Nobody outside of the product team knows or cares about components in the same way.

I once interviewed an engineer who proudly told us that his startup had spent the last 3 months building a beautiful component library which could be accessed by designers and developers. When probed about the success of the startup itself, it soon became clear that since so much development time had been spent on building a beautiful shared component library, the business itself had been neglected. As with all forms of debt, disproportionately allocating resources to tackle component debt will inevitably result in undesirable business outcomes. Proportionality is key, and the product manager’s role is to monitor resource allocation to all forms of debt effectively.

4. Embed

To ensure high quality component-oriented thinking you’re going to need to embed it throughout your team as you continue to build out new forms of value.

This means embedding and enforcing component-oriented thinking by all members of the team in critical parts of the product development lifecycle, including:

- Discovery and design

- During feature development

- Code reviews and release processes

Discovery and design

Designers are often tempted to build every new piece of functionality from scratch. It’s a natural inclination; why bother re-purposing existing stuff when we can create brand new shiny new stuff? Isn’t that what we designers are here for? It’s understandable. But needs to be nipped in the bud.

I once worked on a team where the notification bell went through about 15 different iterations as each new designer had their own favourite version of the notification bell. Should it be a solid block colour? Perhaps it should be a keyline with a colourful hover state? How about a slightly more illustrative approach which looks a little art deco? Frankly, after the fourth iteration, who cares?

Product managers need to make it clear that product designers aren’t necessarily being judged on their ingenious ability to invent new ways of doing things. Yes, there is a time and a place for explosions of imaginative creativity but there is much to admire in a designer who takes a pragmatic approach to building new forms of value by re-purposing existing design patterns.

During the design and discovery phase of a new piece of functionality, ask yourself and your designer some fundamental questions:

The designer’s component checklist

- Have we built or designed this functionality before?

- Can the existing components we already have be re-used or repurposed?

- How might the new feature work using our existing components?

- Is there a reasonable justification for building a new version of a similar component elsewhere? What is that justification? Sometimes there’s a justification; the user task is completely different to the existing component. The job cannot be done in the same way by using the existing components.

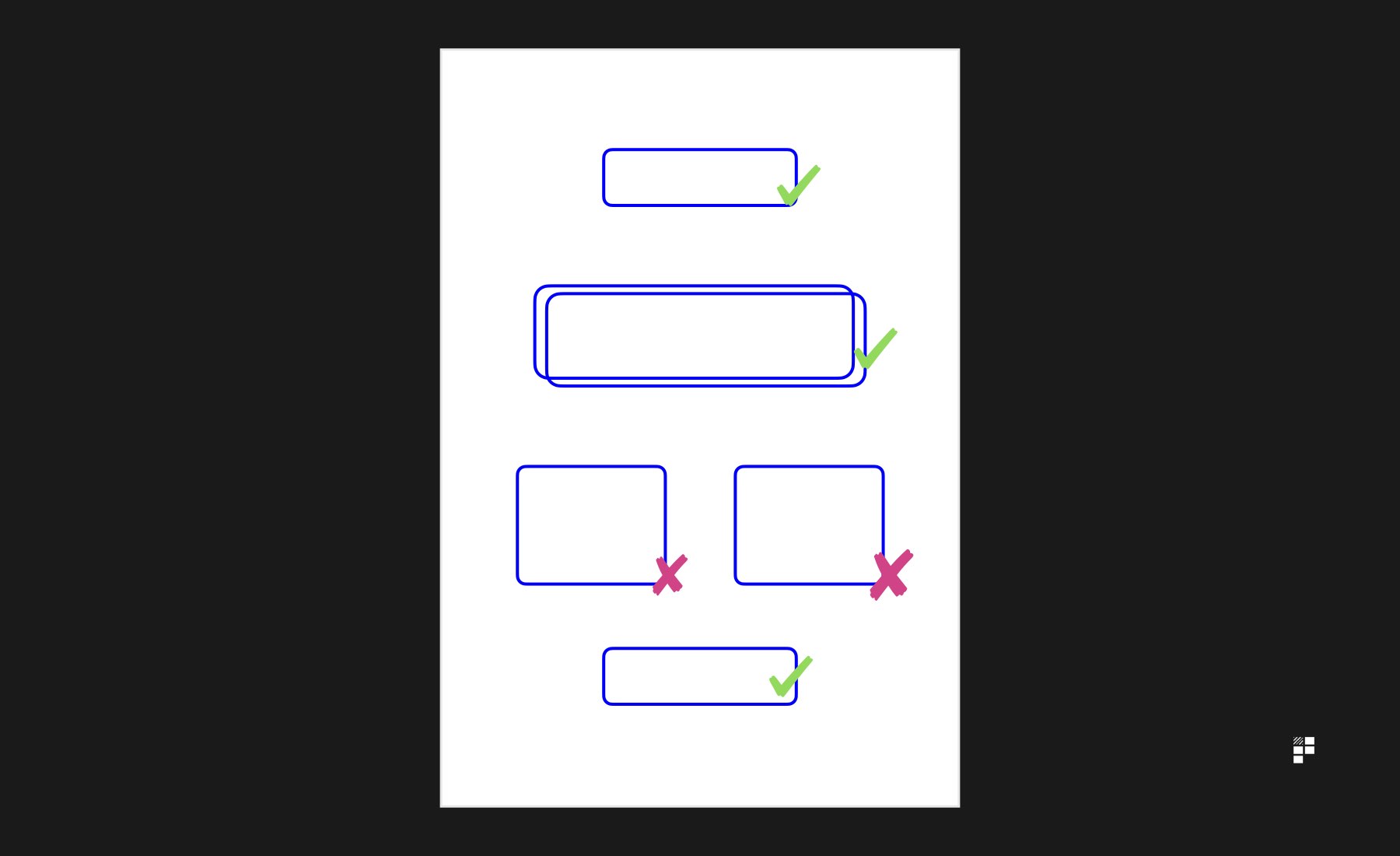

Example – filter on a people page vs filter on a calendar

Let’s say you’re working on a product where you’ve already built a filter component which allows you to filter a list of objects beneath it. This filter was shipped 3 months ago. Your team is now focused on delivering a new feature on a calendar which also requires a filter. Do you build an entirely new filter or do you re-purpose the existing filter? Unless there’s a strong justification for creating a new component, you should re-purpose the existing component.

What’s a strong justification?

In my view, a strong justification is a scenario where by repurposing an existing component you’re detrimentally impacting the user experience so much that the gains in re-using the component are completely lost.

During feature development

Developers, too, need to uphold component-oriented principles if you’re to realise the benefits of using components across the team.

During the development phase, this generally means asking a similar set of questions:

The developer’s component checklist

- What existing components have been built previously?

- Where are they stored? Do we have a place to store them?

- How do I re-purpose them?

- If this needs a new component, how do I build it in a flexible way which allows it to be repurposed in the future?

Componentization as part of code review / release processes

In a product team with strong component-oriented thinking, engineering teams are wired to ask questions about componentization potential during code reviews. This means engineers questioning each other during the code review for front end work which may result in duplication of components.

After a while, it’ll become second nature to most engineers, but it’s important for engineering leaders to push for this type of thinking after having gone to the trouble of creating a strong component-oriented culture. All it takes is a few rogue commits by members of the team before a lack of discipline sets in and you’re back to duplicating components.

Common problems

My engineers want to spend 6 months building a component library, what do I do?

Don’t dedicate 6 months to building a component library. Be pragmatic, prioritise the most important journeys in your UX debt backlog. If you’re a startup that can’t afford to slow down, maybe park the conversation until you’re in steadier waters. Not every team has the luxury of time and resources. If you’re a larger organisation with an established product, perhaps now is the time to take a look at componentization, but just be sure to bring your stakeholders along during the educate phase, otherwise you’ll be (rightly) questioned about whether this is something the product team should be focused on right now.

I work with a remote development team

Establishing a component-oriented mindset is certainly more challenging in a remote set up but you should already have some processes in place which can be modified to help embed a component-oriented mindset. Introduce the component checklist in your discovery, delivery and code review phases. Include component checklists in your remote working tools such as Jira and Trello and host your workshops remotely using digital whiteboard tools.

Where do I start?

Starting can be difficult. Start with the educate / collaboration phases so that you can quickly get a sense of where your product is currently at with regards to components. For future features, the component checklists can be introduced immediately.

Our designers and developers don’t communicate with each other

Part of the product manager’s role in componentization is to facilitate learnings between engineers and designers so that everyone has a shared understanding of the benefits component-oriented working can bring. This isn’t easy, and you’re likely to run into some problems along the way.

In times when designers and developers aren’t working well together, try the following:

- Cross functional standups

- Cross functional retros

- Cross functional planning

- 3 amigos sessions

- Component workshops

- Lunch and learns

- Co-demos with designers and developers

- Pair programming / designing

If these fail, get everyone drunk.

Tools for helping introduce components

- Figma – collaborative ‘Sketch in the cloud’ for designers and developers

- Zeplin – similar to Figma

- Storybook – open source tool for developing UI components in isolation for React, Vue, and Angular

- React – the leading technology for building components