How to de-risk your Product Strategy

At its core, product strategy is decision making; deciding what to build, for whom and why.

Ultimately, you’ll never know if what you’re going to build will succeed until you’ve built it. But there are some sensible steps to take before committing to building your product that will help you to increase its likelihood of success – and de-risk your likelihood of failure.

What are they? Let’s find out.

Stress testing your assumptions

Beneath every product strategy is a series of assumptions. In the context of product strategy, assumptions made by product teams could include things like:

- We can monetize 1% of our audience with a paid for version of the product

- The feature users care about most is X

- Nobody will use this product on a mobile device so we should focus on desktop

- SMEs are a better target market than larger enterprise customers

- We can scale our API capabilities to offer an API-first product to B2B clients

A strategic decision to enter a new market, build a new feature or optimise an existing feature is underpinned by assumptions and product managers should be able to clearly articulate what those assumptions are and what risk they pose to overall strategy.

This can often be quite tricky, but luckily, there are some handy, practical frameworks to help structure the assumptions that underpin your decision making.

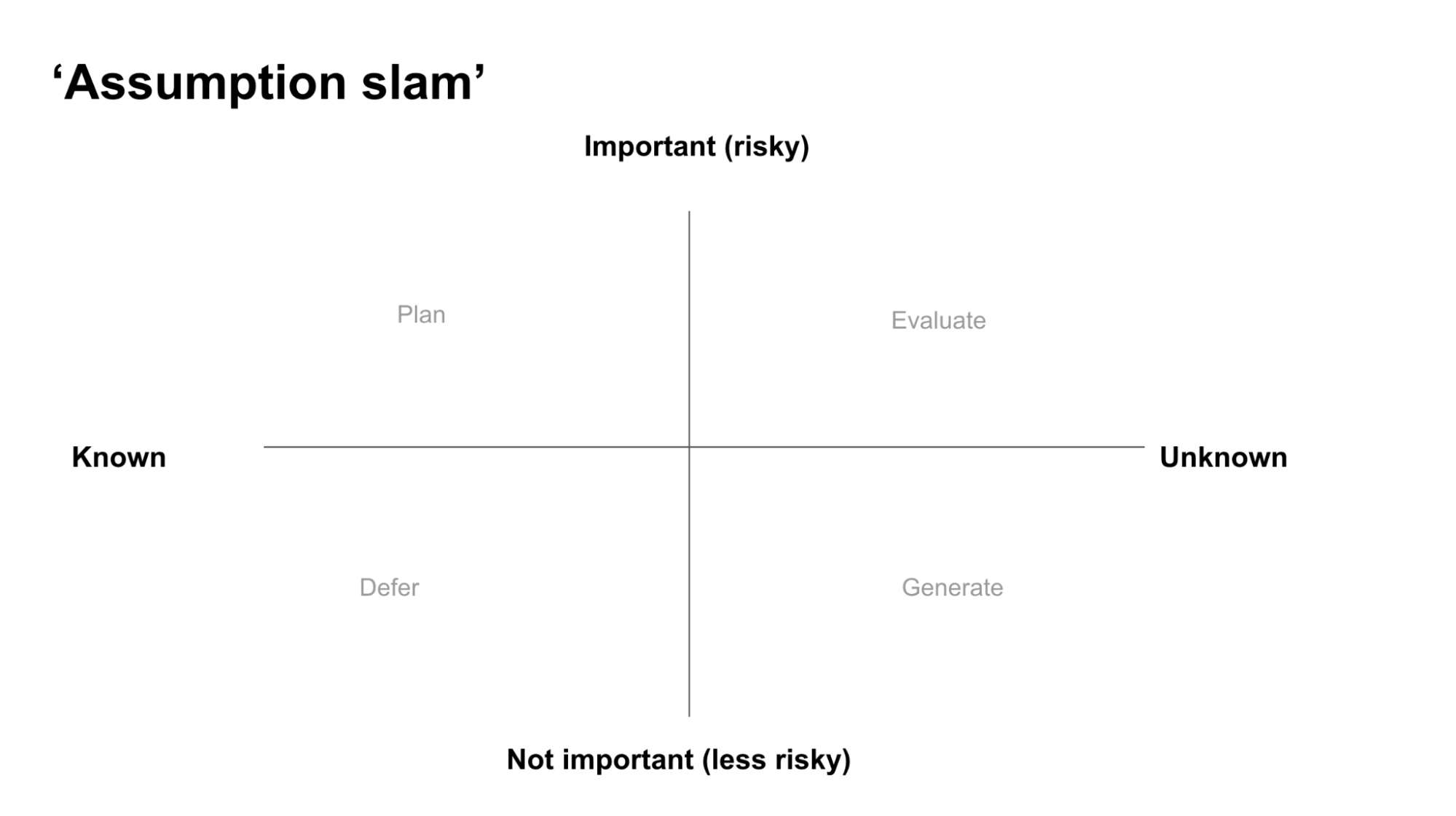

Using Shopify’s Assumption Slam model

Product teams at Shopify conduct what they call an ‘Assumption Slam’. This is a fun way to describe a workshop session and a framework that allows product team members to come together and identify underlying assumptions before kicking off a piece of work.

The framework contains 2 axes: importance and knowledge.

Importance (risk)

How important is this assumption to our strategy or roadmap?

The more ‘important’ an assumption is, the more risk it poses to the strategy if the assumption proves to be incorrect.

For some things, it doesn’t really matter if your assumptions were incorrect, but for others it will prove to be very difficult to reverse course. This is similar to Jeff Bezos’ Type 1 vs Type 2 decision making that we’ve previously discussed.

If you’re worried about the consequences of the assumption being wrong, put it high on the importance axis. If you’re confident it won’t make too much of a difference, mark it lower.

Knowledge (known vs. unknown)

The second axis tests for pre-existing knowledge.

If you’ve already conducted product discovery techniques or you’re armed with solid data that validates your assumptions, you’d put these items higher on the known axes. If you’re still in the exploration phase with little hard evidence either way, they’d be marked as unknown.

Plotting across these 2 axes means you eventually end up with 4 distinct quadrants and suggested next steps for each:

1. Important and unknown (evaluate)

You’re not yet ready to continue since there are unknowns still to answer. Since this is important, an evaluation stage should be the next step to figure out how to answer assumptions.

2. Important and known (plan)

Since these are both important and known, you could consider these as facts at this stage. The next step would be to move to a planning stage, since you’re confident that what you’re going to build is not underpinned by risky assumptions.

3. Not important and unknown (generate)

These assumptions aren’t important (they’re not risky) and there are still unknowns. UX and user research teams could use this as an opportunity to generate ideas on how to

4. Not important and known (defer)

If the assumptions are low risk and known then this is likely to be something you can park and tackle later, if at all.

Using the riskiest assumptions framework

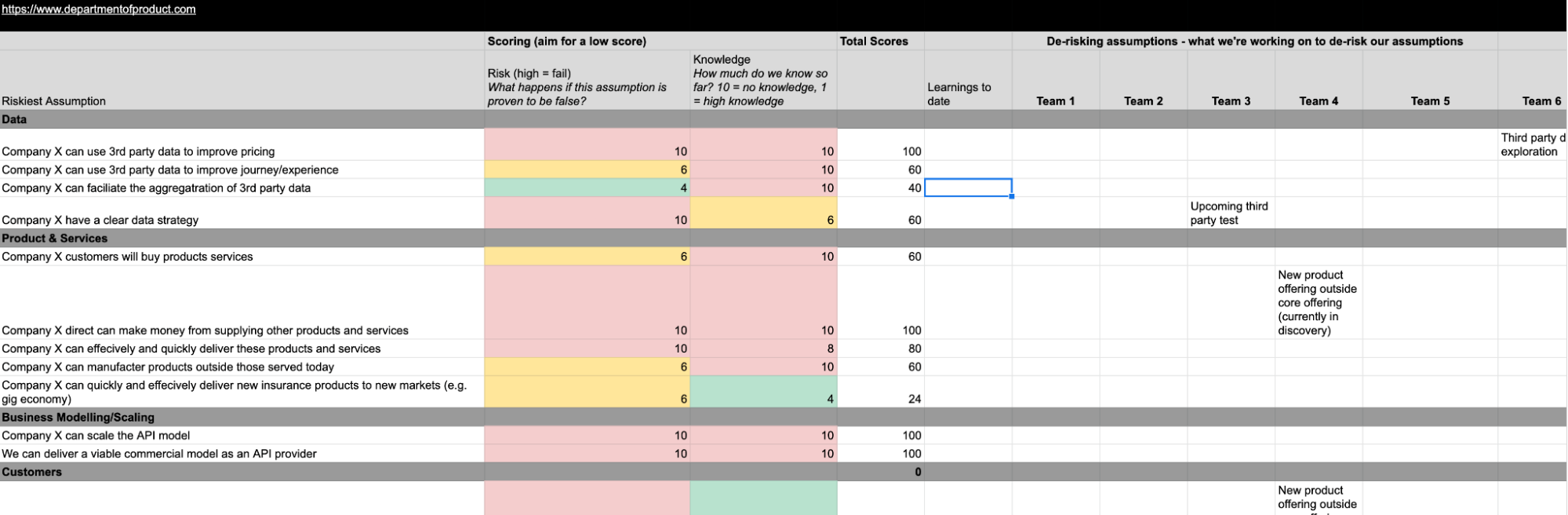

A similar assumptions-based model designed to help you de-risk your strategy is ‘Riskiest Assumptions’.

Just like the assumptions slam, you start by listing your assumptions and knowledge. You then assign each of these a score based on how risky or how much knowledge you have. But the riskiest assumption framework takes things a step further by offering you a way to highlight all the ways each team is actively de-risking assumptions.

So, for example you’d tackle an assumption by declaring that you’re going to run a third party test or by pen testing an API before launching to a high volume customer.

You can check out a version of the riskiest assumptions framework here.

Deploying modern discovery techniques

But de-risking your strategy isn’t just about assumptions; there are plenty of other tools product managers and product teams can deploy to minimise the risk of failure.

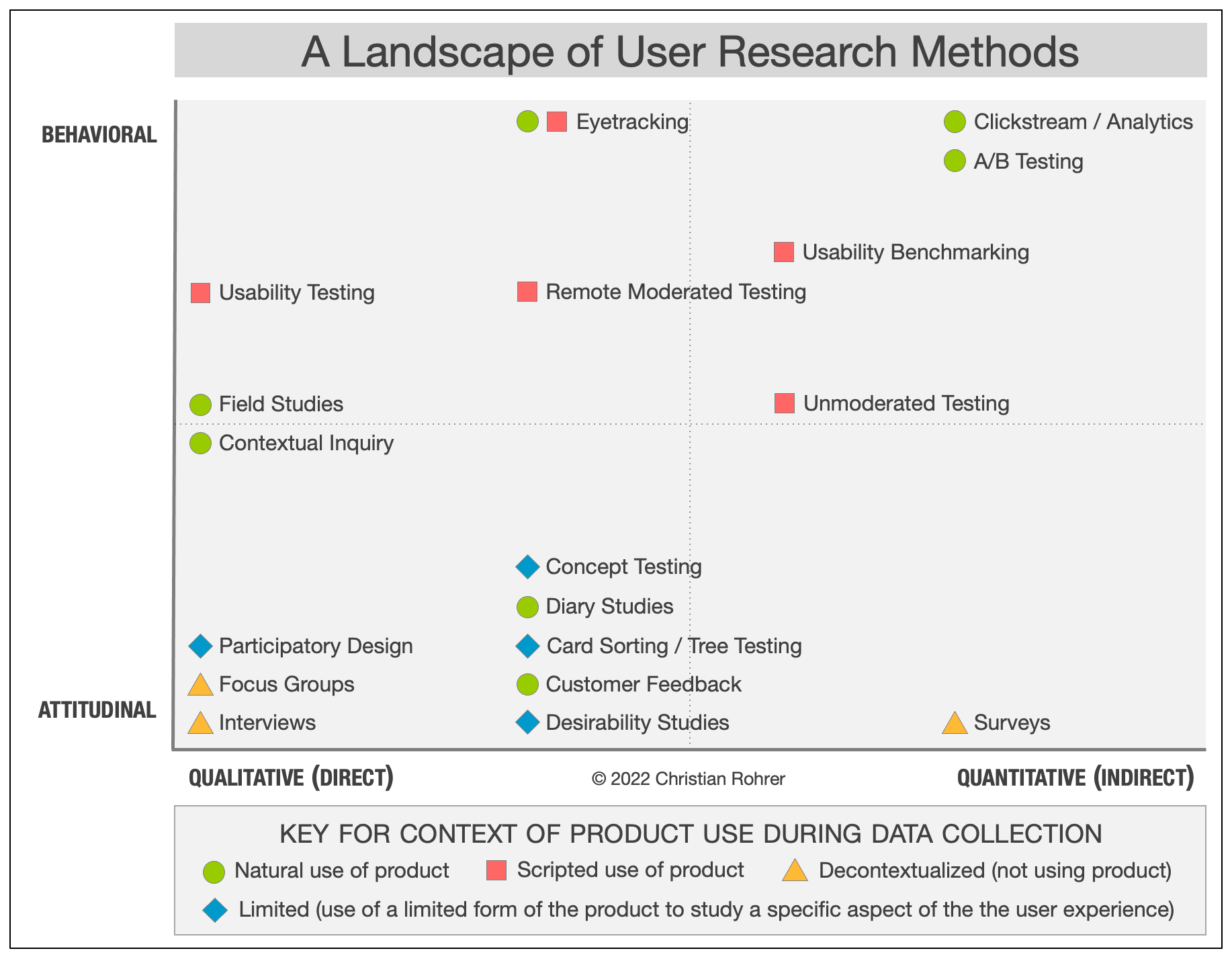

Modern product discovery techniques are a critical part of de-risking, with user research at the heart of many of these. Here’s what the user research landscape looks like:

Clearly, this can all be rather overwhelming for product managers new to the idea of de-risking strategy through user research. This landscape snapshot includes many different types of user research which may or may not be helpful in developing low risk strategic decisions.

Some of the most powerful discovery techniques that product teams can deploy include:

- Interviews

- Diary studies

- Concept testing

- Surveys

Let’s explore each of these to understand how they can help you de-risk your product strategy.

Interviews

User interviews are led by user researchers and involve asking open ended questions to folks who are interested – or might be interested – in using your product.

This type of discovery method is super helpful when you’re considering a brand new feature for your existing customer set or when you’re considering targeting an entirely new set of customers with a new proposition.

Many product teams are excellent at speaking to existing users to understand their problems (and users are always happy to oblige in telling you their problems), but where many teams struggle is to explore nonusers of their product before deciding to enter a new market.

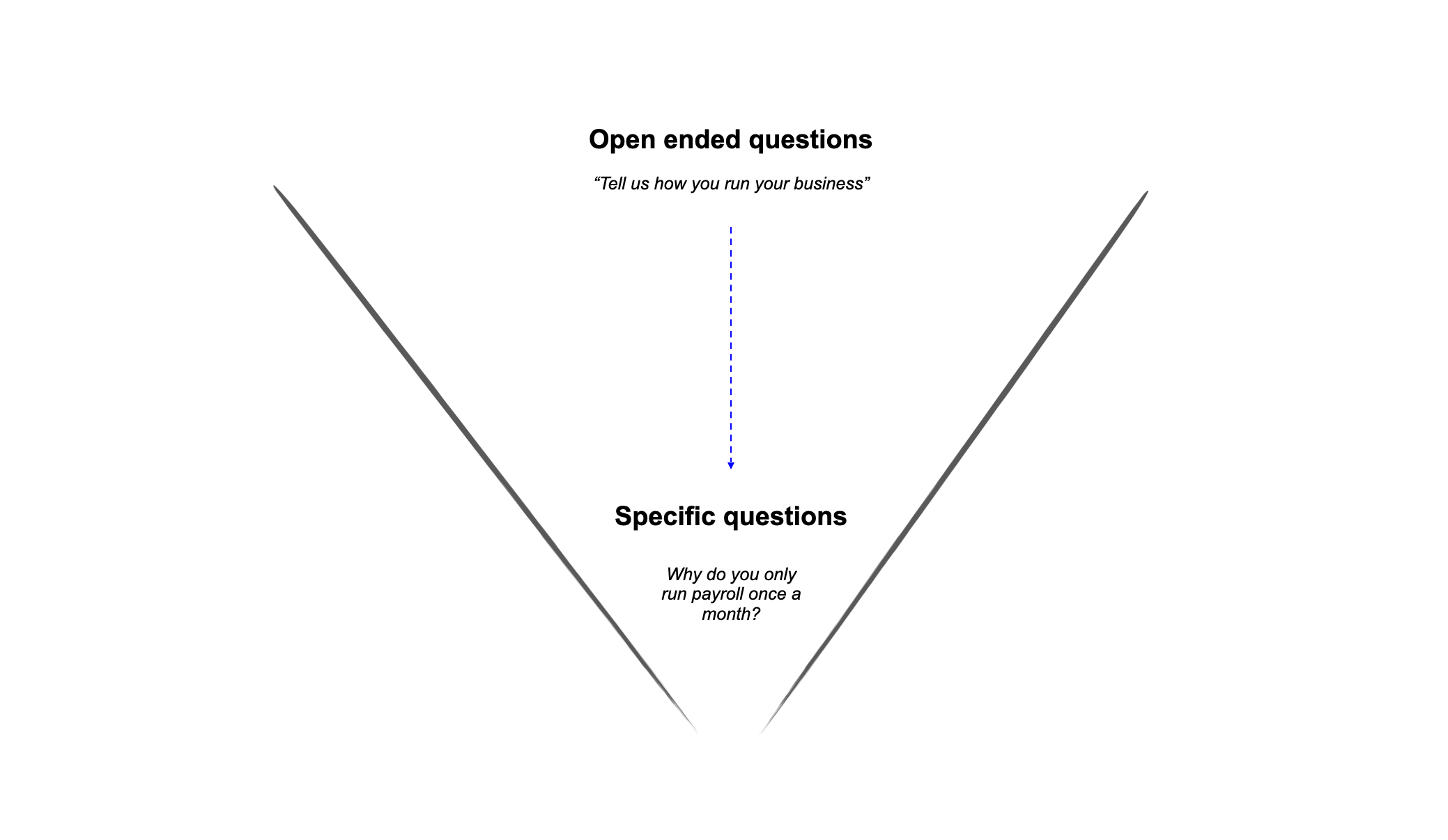

Excellent user researchers will keep the conversation open ended and free flowing with open questions followed by more probing questions to get to the nitty gritty of the details that matter.

Crafting a customer-centric product strategy means speaking to customers (and potential customers) regularly. Arming yourself with a bunch of solid interviews with users in your target segment can help to de-risk your strategy far more than other methods.

Diary studies

Whilst user interviews are extremely valuable, they’re not without their downsides.

Users don’t always do what they think they do. They’ll tell a user researcher that something’s important to them but anecdotal evidence is different to behavioral evidence. What users say they do and what they actually do can sometimes be two different things!

That’s where diary studies can be super helpful. Why?

Well, diary studies don’t rely on a conversation between a user and a user researcher where users are asked questions about their previous behavior. Rather, a diary study is longitudinal and ongoing and is designed to capture real behaviors, rather than anecdotal recollections. Unmoderated behavior can often be more reliable than moderated.

Participants sign up for a period of time (let’s say 4 weeks) and they’re monitored in some way, with feedback mechanisms in place for collecting real time data.

Tools like Dscout can be excellent for this kind of thing. I once used Dscout for a startup where we monitored users over a 5 week period and it was fascinating.

In a product strategy context, you can give participants a series of tasks to complete over a set period of time, or give them a clickable prototype to ‘use’ over a period of time to understand if your assumptions are correct and / or your product is valuable.

Concept testing

Concept testing is used to gauge a user’s response to a product offering. This can be an extremely helpful and lightweight method for testing product strategy.

It can take many forms, but one of the most powerful ways to do this is to take the Amazon press release style document and translate this into something a user can read / consume and provide feedback on.

The Amazon press release docs are typically used for internal purposes but they’re written in a consumer friendly way. Product managers write up a consumer-oriented summary of the product offering and internal stakeholders provide feedback before deciding whether to pursue a particular opportunity.

Concept testing takes this a step further by involving customers in that part of the process too.

Just as you’d summarise the core offering in a press release designed to be viewed from a customer’s perspective, with concept testing you can actually involve potential customers to get a sense of what they think about the offering, too.

Other types of concept testing

- Comparison testing – all respondents are given two distinct concepts and are designed to rank or rate the two different product concepts.

- Sequential monadic testing – a monadic test is where participants are shown one or more concepts in isolation – as opposed to two at the same time for comparison purposes. Groups of respondents are split up and are shown all different variations of a product.

- Protomonadic testing combines comparison testing with monadic testing, giving participants the opportunity to see product concepts and features in isolation followed by a comparison.

Surveys

Often underrated or seen as a little too simplistic by some, surveys are an excellent way to sense check whether your strategic decisions are going to be successful.

Surveys are useful for identifying pain points which can then be translated into solution-oriented ideas.

For example, a survey might ask:

As a HR assistant, which of the following activities takes up most of your time (rank highest to lowest):

- Running payroll

- Managing holiday

- Dealing with internal issues

- Helping with legal problems

You could then use this to back up a strategic decision to focus on creating a payroll solution for HR managers, for example.

The wording and design of a survey is a skill that is best handled by user research professionals since the results can be massively skewed, depending on how the survey has been designed.

And this leads us nicely on to the final suggestion on how to de-risk your product strategy: using data.

Data-informed decision making

In my view, strategic decisions should rarely be made without some data which suggests that your decision / bet is likely to be successful.

In the context of product strategy, data could include:

- Market data – trends demonstrate that X is happening, therefore we need to do Y

- Product usage data – analytics shows that feature X is not used despite significant marketing efforts. Therefore, we should kill the feature and focus on X instead.

- Geo data – we know that X% of our visits are coming from Ireland, therefore we believe this is a clear indicator that we should launch a product for Irish consumers.

- Research data – our research studies show that X% of customers would use X.

- Business data – our lifetime value has increased since we released feature X. We should explore similar opportunities to further increase our LTV.

Data and the power of experimentation

One of the most powerful ways to arm yourself with helpful data is to conduct experiments. In this context we mean experiments that are separate to your research activities and experiments that are at a strategic rather than tactical level.

A tactical experiment might be to remove a step of a payment process or to change a CTA on a landing page. These may result in a % uplift but aren’t so fundamental that they impact your product strategy.

In contrast, a strategic experiment would be more concerned with fundamental questions of what you’re building, for whom and why. In this context, you might run an experiment to test for demand of an API marketplace, you might build a clickable prototype of a new feature and send it to a bunch of customers in an email or you might build a real lightweight version of a feature and toggle it on for a subset of customers.

Bringing it all together

Good product strategy is about clear decision making. It inevitably involves trade offs: deciding what to do as much as deciding what not to do.

And that’s why so many businesses struggle with it; we’ve all worked for CEOs or execs who constantly change their mind or refuse to commit to a specific direction for the fear of missing out on all the other possible alternatives.

But the truth is, even in larger companies, you can’t do it all – and you shouldn’t try to do it all. Being clear about what paths to pursue is essential for building a winning strategy. You’ll never know until you actually build something whether or not it will work, but by using some of these de-risking tactics, you’ll give yourself the best shot possible.