Managing UX debt

Why tension between product designers and managers is healthy

I was recently asked by a colleague what I found to be the most challenging aspects of product management. Without much thought, I blurted out a response which surprised me a little. ‘Managing the relationship between design and engineering whilst trying to build a great product’ – or words to that effect. What I was trying to articulate was that I often found it very difficult to find a balance between what’s beautifully functional and what’s feasible in the timeframes available.

My colleague, a user researcher, actually had no idea that this was something product managers struggled with and since speaking to other product colleagues it seems to be a common challenge.

What is UX debt anyway?

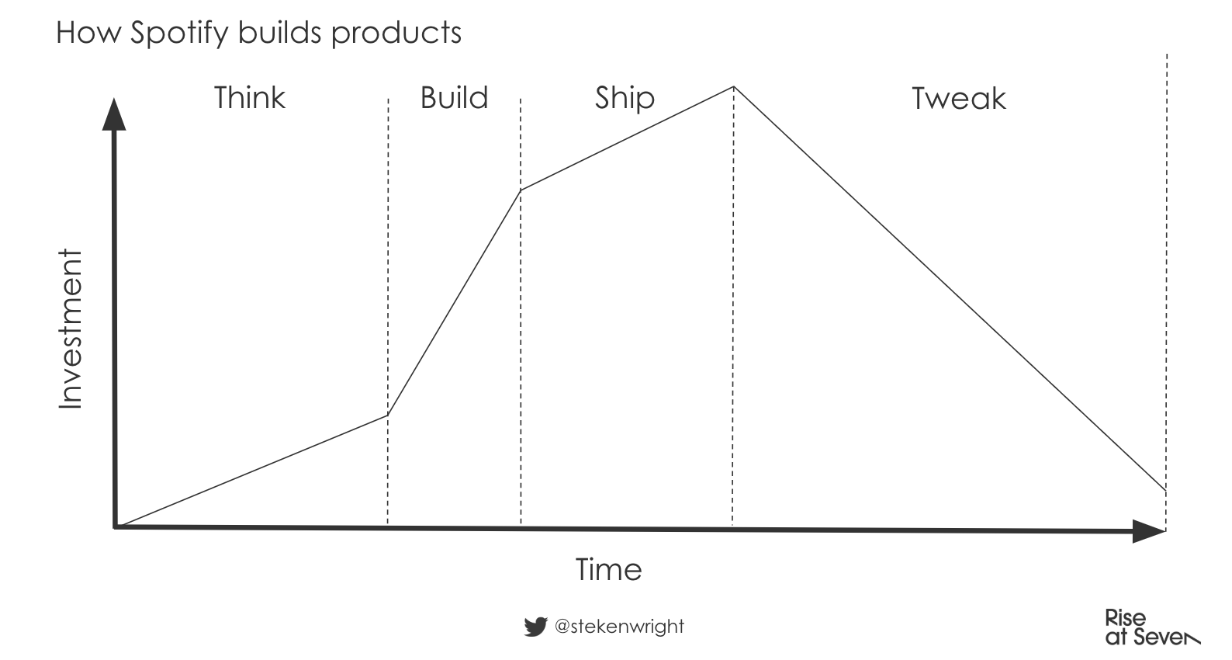

Just like tech debt, UX or design debt, is the same principle applied to the design of your product. It means you’re fully aware that your user experience isn’t optimised to its full potential, but in the interests of time and given the resources you have available, you make a decision to limit the scope of your solution so that it still solves a user need in the knowledge that your first version isn’t as beautifully elegant as you might like it to be.

It is possible to iterate your way to the a more elegantly designed version of your product and it is the product manager’s role to help instil this iterative mindset into the team and to manage any fallout from approaching design in an iterative way.

4 steps to managing your UX / design debt effectively

For the times where you and your team know you’ve had to release a compromised first version of your product which doesn’t quite meet the pixel perfect original designs, here’s some practical things you can do to manage your UX debt:

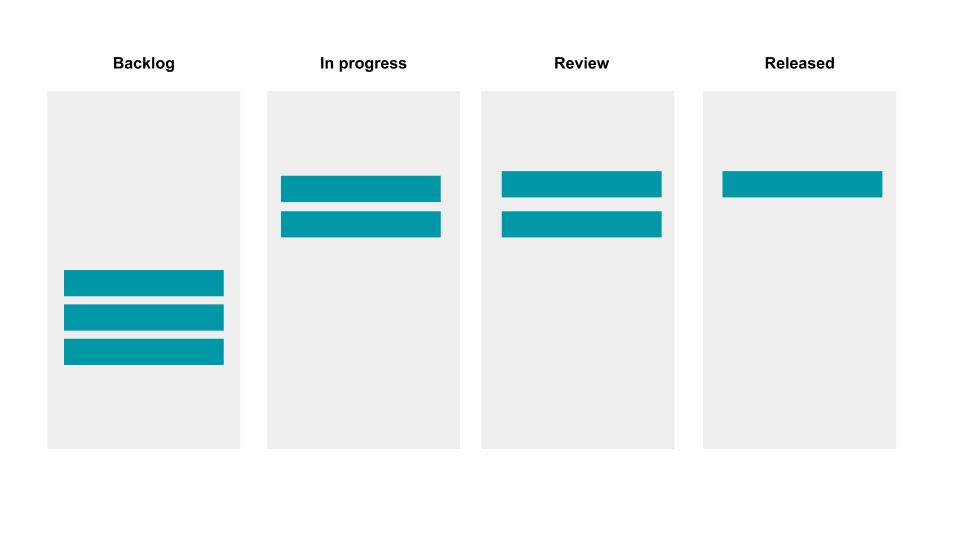

1. Keep a UX / design debt backlog

Just like a tech debt backlog, the UX / design debt backlog is something which needs to be tracked.

Firstly, figure out why the UX debt occurred in the first place. It could be the result of conscious decision making by product teams. That is, you know you’re making a compromise for v1 and you’ve discussed why it’s OK to live with the compromises for now.

If your UX debt has been incurred as a result of sloppy development, that’s a different problem which needs to be addressed by speaking to the engineers responsible instead.

2. Prioritise based upon the user journeys the debt impacts

Different types of UX debt will have a greater impact on your product depending on the journeys – or user goals – they impact. Some user journeys are more important than others.

Whilst you might be able to live with a design issue which causes a component to render badly on tablets on your invoice generation page, the same problem on your ecommerce checkout or your user onboarding journey will likely have a greater impact on your users – and your business.

Regular user testing sessions will help you identify new UX debt on a regular basis – and you’re likely to find more problems than you’ll ever be able to solve. Prioritisation and knowing what’s important and what’s less important is critical for managing types of UX debt.

Use your product strategy and relevant data to identify your most critical user journeys and prioritise your UX debt accordingly.

3. Allocate time for UX debt clear ups and hire skilled front enders

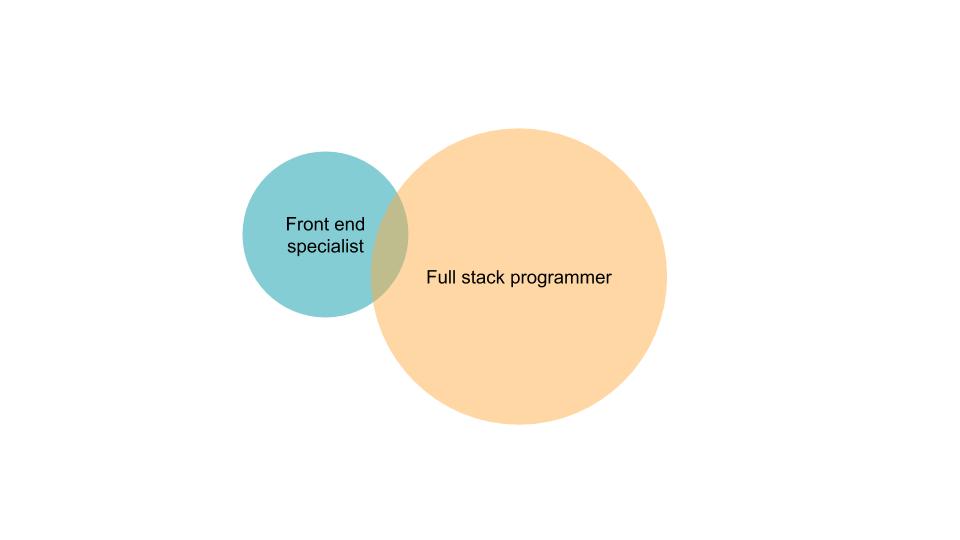

The rise of javascript and the so-called ‘backendification’ of front end development means that there are fewer 100% front end engineers in many teams, but there may be a case for hiring developers who lean heavily towards the front end side.

In my experience, since the lines between front end and back end development have become more increasingly blurred, hard core programmers sometimes care less about finessing the visuals on the front end than a traditional front end developer might.

If you have the budget, it might be worth hiring specialist front end engineers who can address UX deficits since they are more likely to have an eye for the smallest design details than perhaps a traditional programmer might. Pair ‘programming’ between front end developers and designers can help. And just like you might allocate a % of work to tackling tech debt, you can address UX debt in similar short bursts of activity.

4. Prevent UX debt through design reviews

Just like code reviews, design reviews add an additional filter for assessing work before it gets pushed out into the wild, which should prevent UX debt accumulating in the first place.

In my experience, including a formal design sign off / review for important new features at least, can help to bring designers and engineers closer so that they both understand the complexities of each discipline. It makes sense for the product person to take part too so that your engineers don’t spend 2 weeks on aiming for pixel perfection but overall having a formal design sign off process for important new features, definitely adds value and should result in less UX debt in the future.

Managing the tension between product designers and product managers

As product teams we make trade-offs all the time. One of the most difficult trade offs is knowing where a design meets the challenge of being an elegant solution to a problem without overspilling into the pursuit of perfection.

The relationship between product designers and product managers can – and arguably – should be – littered with tension at times. It’s perfectly healthy. As the former director of product at Tinder once recommended:

Work with people that make arguing enjoyable.

— Norgard (@BrianNorgard) April 2, 2019

How to have healthy arguments with designers

Here are some practical ways you can facilitate healthy debate without descending into an unhealthy war of words:

- Generate options – the more design options you generate as a team, the less likely the debate will degenerate into an adversarial battle. Reducing your options to 2 means digging deeper into your positions is more likely if you disagree. Expanding your options has the opposite effect.

- Use objective language – I learned this one the hard way when I kept using horribly personal language like ‘your design’ or ‘your approach’. This unnecessarily personalises the design debate. Use language which refers to ‘our approach’ and ‘our goals’ instead. And always start with the benefits of the approach you disagree with to acknowledge the fact that there are plenty of merits to it.

- Refer to objective data – if you’re stuck at an impasse with no clear way forward, try to get some data to help shape your decision making. This could be data from your analytics suite or qualitative data from your last round of user testing. Any form of data will help shift your mindset away from the designs in front of your eyes and onto the objective reasons it may or may not succeed.

How do you know how much UX debt you can live with?

It’s difficult to come up with a hard and fast rule which can be applied to all design decisions, but ultimately you can (and arguably should) live with a certain amount of UX debt so long as your product is addressing the needs and meeting the goals of your users.

Indirect indicators of healthy UX debt levels could include:

- High task completion rates

- High activation rates for critical tasks

- Repeat usage

- Low churn

The product skill which is perhaps the most difficult to articulate is the ability to sense where a compromised solution still meets the needs of users whilst keeping your designers, developers and users happy at the same time. Juggling those three interests isn’t easy and it’s a skill which improves over time.

But what about cases where design / UX is our differentiator?

Yes, there is also a strategic consideration at play here too which is worth noting.

It may be that one of your differentiators as a business and a product is your UX / design. In these cases, I’d argue that your tolerance for design debt should be lower than in companies where your UX / design isn’t one of your explicit differentiators. This may mean more development time spent on pixel perfection, but it’s time well spent.

With increased competition from both industry giants and upstarts alike, the amount of scope for UX debt is decreasing as user expectations increase. Nonetheless, a little pragmatism – as is often the case with many aspects of product development – is the critical factor in managing UX debt effectively.