Product Monetization Strategies

Bridging the gap between creative and commercial thinking

Does generating revenue matter?

A business is a repeatable process that makes money. Everything else is a hobby.

—Paul Freet, Commercialisation Expert

This is a neat way of summarising the definition of a business. But is it true? Does making money actually matter?

If a product has no monetization mechanisms built into it, it’s usually (but not always) 1 of 3 things:

- An experimental product / department inside a well-funded larger corporate which can afford to lose money

- A venture backed startup which has yet to monetize in any meaningful way but has the necessary funds to keep the lights on and is demonstrating growth

- A side project you work on for fun which may never become a business. And that’s OK.

Ultimately, if a product is to succeed as a business it needs to prove it is a business.

And the only way to do this is to generate sufficient revenues to either pay the bills, pay investors or to incentivise investors to put more money into the business on the premise that revenues will ultimately one day increase to the point where the business becomes viable.

Having spent a few years working in the advertising industry where the monetization of everything is second nature, it’s often been fascinating to work with folks who not only struggle to think commercially but also actively avoid exploring ways to monetize products and generate revenue because doing so somehow makes them a bad person who is fixated on cash.

What is monetization?

The word monetization sounds dirty, doesn’t it? It sounds like you’re planning to exploit your product’s users in some way to dupe them into paying for something they don’t want in order to generate cold, hard, evil cash.

The same thoughts appear when you ask someone to think of salespeople, selling – or the opportunity to pursue a career in sales. The thoughts that spring to mind are of somehow being tricked into buying something you don’t want.

Sales is dirty.

Money is dirty.

‘Monetization’ is very dirty.

Sure, there are plenty of examples of where companies have gone too far in monetizing their product, invading users privacy and destroying the user experience, but that’s monetization and sales done badly.

Monetization is the process of deriving revenue from the value you offer to your users.

Your product – if it’s a product worth using – is delivering meaningful value to its users in some way. It’s only natural therefore that you can expect to receive something in return – including revenue. This revenue may or may not come from your users but it’s fair to suggest that in exchange for the value you offer and deliver to your customers, you can expect to be able to derive some form of remuneration from somewhere in return.

The difference between revenue and profit

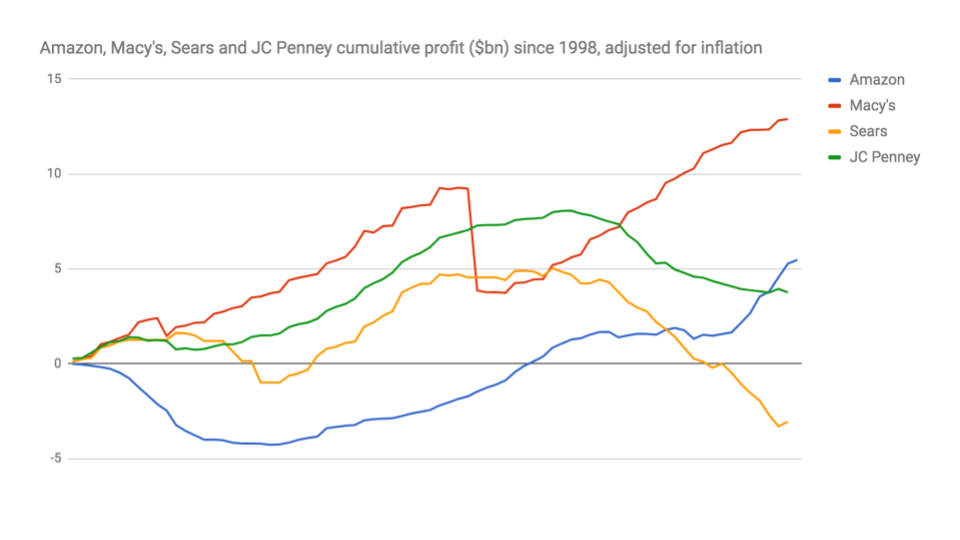

For over a decade, Amazon didn’t make a profit. It’s primary focus is – and arguably always will be – to provide extreme value for its customers. How? By offering the cheapest possible price on the goods it sells by cutting costs and ploughing money back into the business to drive efficiencies where possible.

Amazon could sit pretty on top of a huge cash pile but instead chooses to enhance its value proposition by offering cheaper prices through razor thin margins and loss leaders.

It’s large enough to experiment with new loss-making product ideas (Kindle Fire Phone, anyone?), put competitors out of business and branch out into web services because its commitment to delivering value through its core business and not chasing profits is what continues to underpin its success.

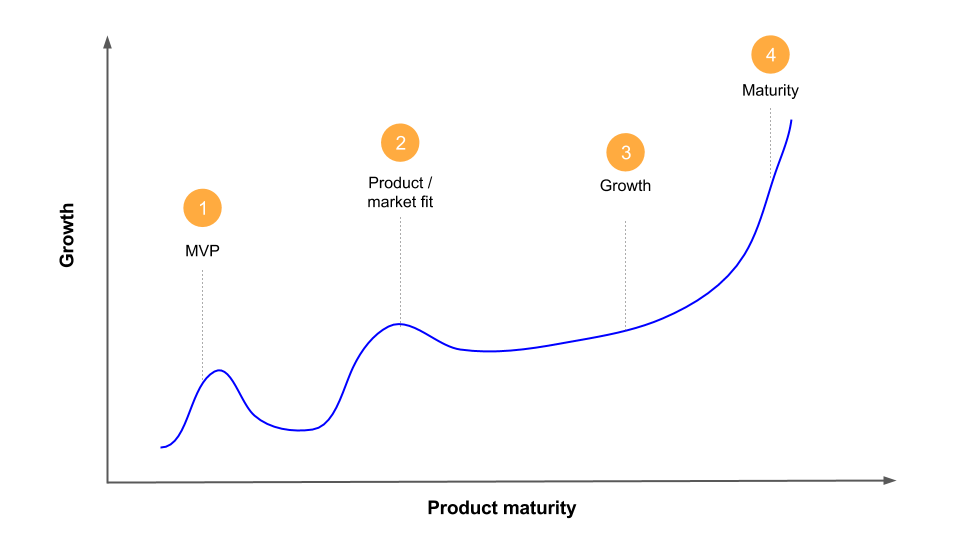

Monetization, startups and the product lifecycle

Some products will have monetization mechanisms baked into their model from day 1. Others will need to achieve scale before they have a solid platform which can be monetized later.

Indeed, it’s arguable that too much focus on monetization in the early stages of your startup could inhibit growth. Would you have an Instagram account if you had to pay £5 a month for it? Would you ever have tried Spotify if the only option was to pay $9.99 a month?

Your monetization strategy is linked to the stage of your product’s lifecycle / business.

Some startups won’t focus on monetization at all. Instead, they may be acquired purely on the basis of the technology they’ve built or the talent they’ve recruited.

If you’re a startup and you know upfront that you’re not seeking to generate meaningful revenues until you have reached X number of users, make this decision clear and set your investment / growth goals based upon this.

Even if you don’t have revenue generation baked into your product from day 1, it’s still worth considering what your revenue streams might be in the future. If there is a no potential path to monetization in the future this can be problem for your product and for your business.

Startups which struggled to find a path to meaningful monetization

- YPlan – the London-based events app, a simple, neat product with a complex monetization mechanism. Acquired for a disappointing $3m after raising more than $40m in VC funding.

- Soundcloud – the struggling audio company has failed to find a way to generate meaningful revenues. Its monetization mechanisms are muddled and it continues to look for a buyer or funding amid fears it has just months in business remaining.

- Fab.com – the doomed ecommerce brand raised a ton of cash but a series of maniacal pivots in an attempt to find a path to profitability ended in the company being sold off at a huge loss to investors.

As former Fab.com CEO Jason Goldberg eventually put it: ‘You can’t pivot your way to a business model’.

Guiding principles for monetizing your product without pissing off your users

Product managers are burdened with having to walk the perilous tightrope of achieving business results (including revenue targets), without pissing off users. In fact, the challenge is greater than merely avoiding pissing off our users; it is to make our users genuinely delighted, whilst the money rolls in to keep our business / investors delighted – all at the same time.

There are a few guiding principles which are helpful to consider when generating ideas on how to monetize your product:

- Complement the user experience

- Think long term

- Be creative

1. Complement the user experience

‘We don’t want to adversely impact the user experience’ – Product Manager.

‘We fund your salaries, dear.’ – Sales team.

If you’ve ever worked in an organisation which has a product and an advertising (or other) sales team which are interdependent, you’ll know that exchanges like this can be fairly commonplace. For the sales team, their target is what matters most. Bad sales people will be more than happy to bastardize their product to achieve revenue targets without considering about how this may impact the user experience. Good sales people will understand that the key to long term revenue generation lies in the delicate balance between achieving quarterly targets and building a product that people still want to use.

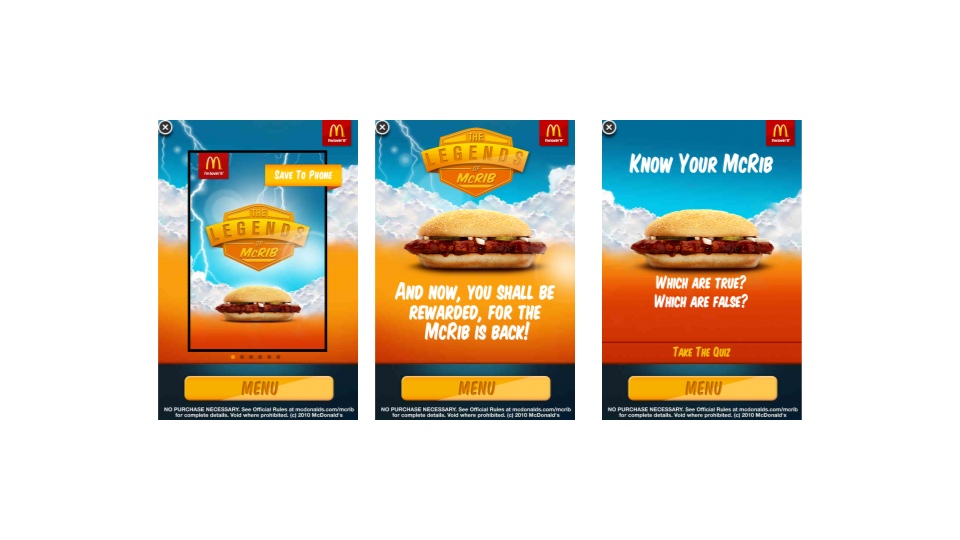

I once worked in a team which ‘commercialised’ the homepage by selling a £50k 1 day ‘home page takeover’ to McDonalds. This was an awesome deal for the sales team. The additional revenue meant the team had reached their target and would get a bonus. For the actual users of the site however, this meant they would be greeted by a hideous McRib burger whilst planning a luxury health spa trip. Hardly a complement to the overall experience but on the flip side, arguably not so painful as to drive users away forever.

How to complement the user experience

Where possible, monetization should at best complement the user experience and at worst do nothing to negatively impact the user experience:

- If you’re selling ads or working with commercial partners, pick partners which suit your target audience and can actively add to value to your users

- Price your product in ways which make the jump from free to paid more manageable and attractive for different segments of your audience

- Incentivise your users to give you the assets you need for monetisation by giving them a choice. For example, if your product is an app, don’t force your users to share contacts and personal data up front so you can sell sponsorships. Instead, build a product which your users want to share with other contacts and be honest and be up front about your commercial needs.

Before you commit to a monetization strategy, test the idea on a few users and measure how this impacts the experience. Use your NPS as well as qualitative feedback to measure the impact. If the reaction is outrage, consider alternative monetization methods.

2. Think long term

It’s easy to chase short term deals and revenue targets to achieve growth, but the key to smart monetization strategies is to force yourself to think longer term.

Sure, for startups this can be difficult. If you’re faced with an opportunity to commercialise a part of your product which means you’ll get funded it might make sense to take the cash and continue growing. However, be aware that your decisions may have a long term impact on your key product metrics.

3. Be creative

Monetizing your product can be a stimulating, creative process. Forget the conventional nonsense of advertising as being the only way to monetize your product. There are plenty of creative, innovative ways to generate revenues for your product.

5 practical ways to monetize your product

Whether you work at an early stage startup or at larger corporate, being able to quickly ideate monetization strategies is a powerful skill to have.

Here’s some suggestions on practical ways to monetize your product, along with some examples for each:

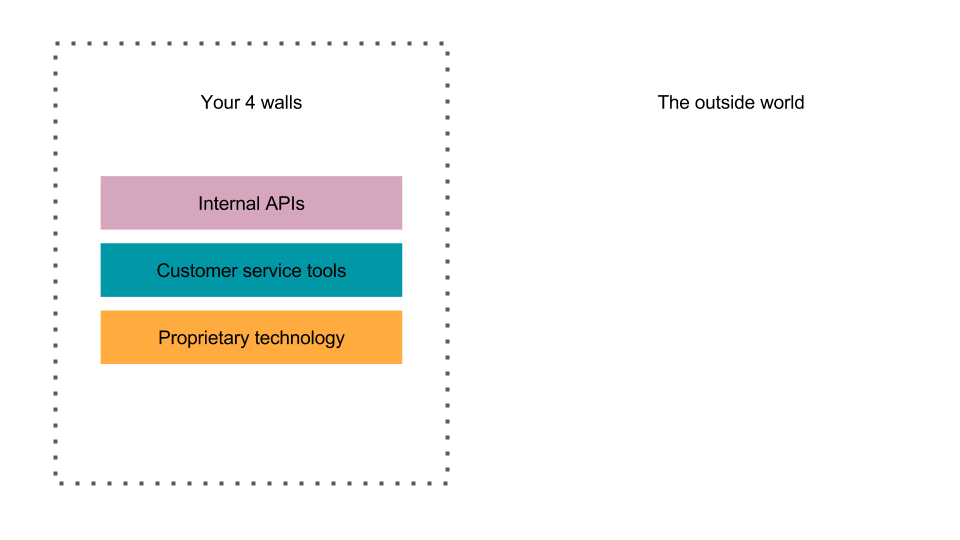

1. Commercialize existing products or technology

You may be sitting on a trove of additional revenue streams without even realising it. How?

Aside from the core value your product delivers to your users, your business will no doubt have additional tools and technology which have been built to support the infrastructure of your business.

For example:

- You may have a top-notch set of customer service reporting tools which connect to third party APIs and provide revenue forecasts for the next 2 months.

- You may have an API which is being used only by your engineers internally to perform a specific business function

- You may have an invoicing automation algorithm / process which is being used to generate global invoices in 25 currencies

These products or technologies are analogous to your core product offerings but can and do provide value themselves.

Consider how you may take each of these products / services and commercialise them in ways which may bring in additional revenues for your business:

- Are there other companies in your vertical or other verticals who may need the customer service tools you’ve built?

- Are there opportunities for making your APIs public or exposing these APIs to 3rd parties and charging an ongoing fee for access?

- Is it possible to take your invoicing automation technology and package it into something more meaningful which can be accessed by external customers?

Amazon’s AWS now accounts for a greater share of its operating income in North America than its core ecommerce business, which is pretty astounding. How did AWS start? It was originally built as an internal product to support the infrastructure of its core business and then commoditised into a product for external customers.

Working closely with your technical architect and conducting regular tech audits can force you to take stock of all of the resource you have in your organisation which can help you to consider ways in which you could monetize these.

2. Subscriptions

Subscriptions work by offering ongoing value in exchange for ongoing payments.

You can choose to only offer your product through a subscription or you can choose to upsell additional value through subscription models by offering a multi tiered approach to your value delivery.

Subscriptions are an attractive monetization mechanism because they are a predictable and reliable source of income which will help with forecasting and revenue modelling.

The vast majority of your users won’t want to pay for anything, so you should tread carefully when considering introducing subscriptions.

Some questions to ask yourself before introducing subscriptions include:

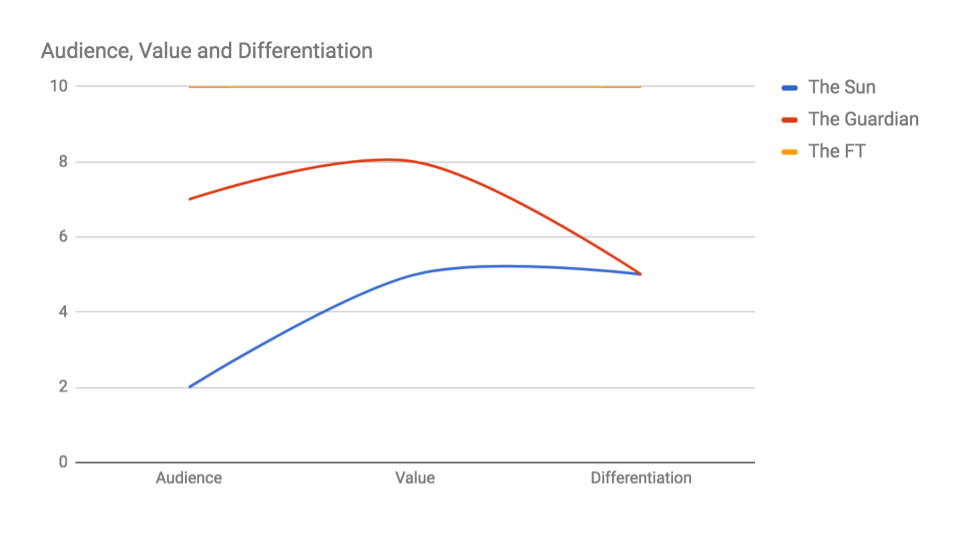

- Audience – is our audience willing and able to pay for a subscription-based service?

- Value – is our offering valuable enough for someone to pay £X per month for ongoing access

- Differentiation – is our product sufficiently differentiated to prevent our customers getting a free or similarly priced alternative elsewhere?

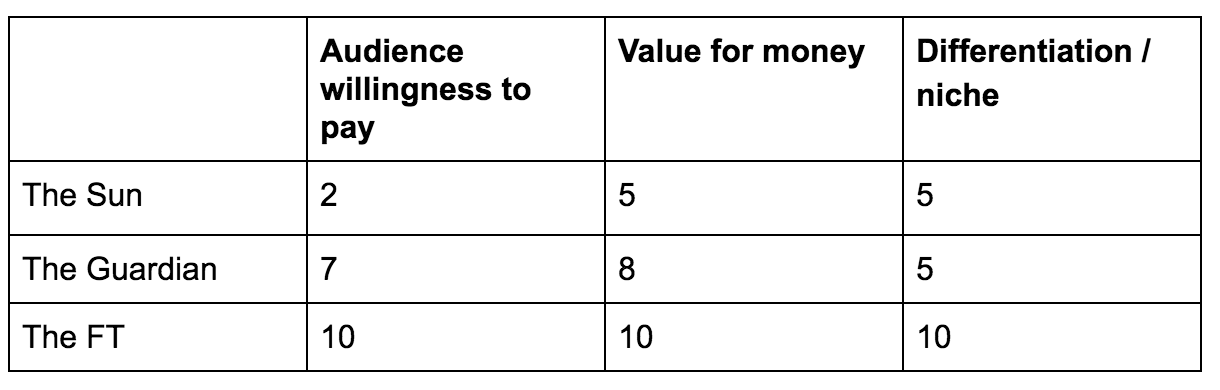

Example 1: the newspaper industry

The newspaper industry has grappled with subscriptions for years, with varying degrees of success.

Let’s consider 3 newspapers with 3 distinctly different approaches to the subscription model: The Sun, The Guardian and The Financial Times.

The Sun

Originally free to read, The Sun introduced a paywall, saw visitors decline sharply YOY, ditched the subscription and reintroduced free to read. A resounding failure.

The Guardian

Has stuck with to free to read but in the face of declining revenues looked to alternative revenue streams including ecommerce and books. Recently revisited the paid for subscription model but positioned it as a ‘membership’ – using language similar to the wikipedia’s donation messaging, linking revenue to its ultimate survival as a business. Limited success so far.

The Financial Times

Introduced a paywall with an allowance for viewing a few free articles a month. The FT recently reported profits and its revenues are solid, thanks in part to an increase in its digital subscriptions business. A success.

These 3 differing approaches to introducing a subscription model into the same industry demonstrate how flexible and creative you can be when introducing subscription models into your product. It’s clear that the FT is best placed to succeed in the news subscription marketplace:

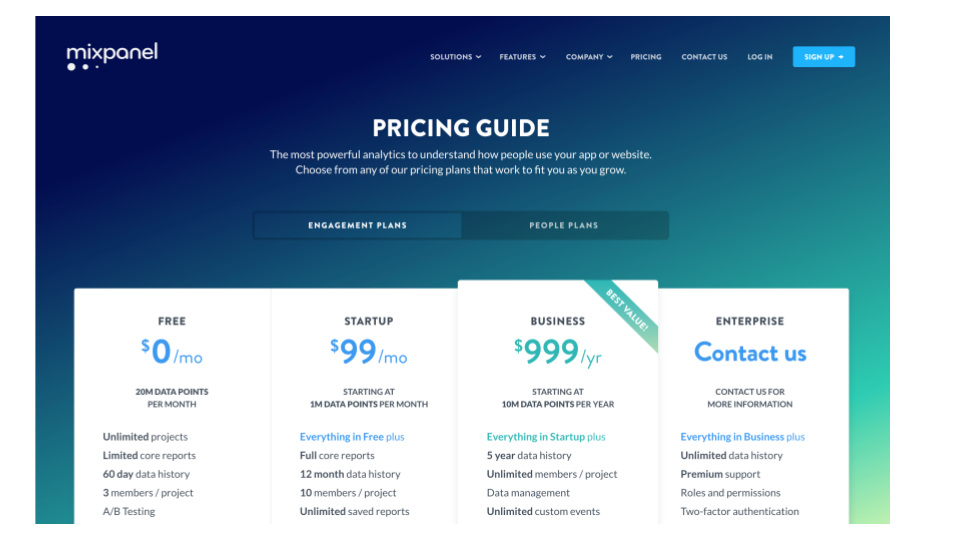

Example 2: SAAS businesses

In software as a service businesses, the recurring subscription model is the most popular. The value i.e. the service that the software is providing, is usually behind a paywall of sorts.

Selling SAAS on a subscription basis feels natural;

- The transition from free to paid is typically through the completion of a trial period which feels less forceful than transitioning from free to paid in other verticals – including news / content sites.

- SAAS products are typically sold B2B which means the buyer is typically a business, not an individual, pushing up the cost per month and LTV

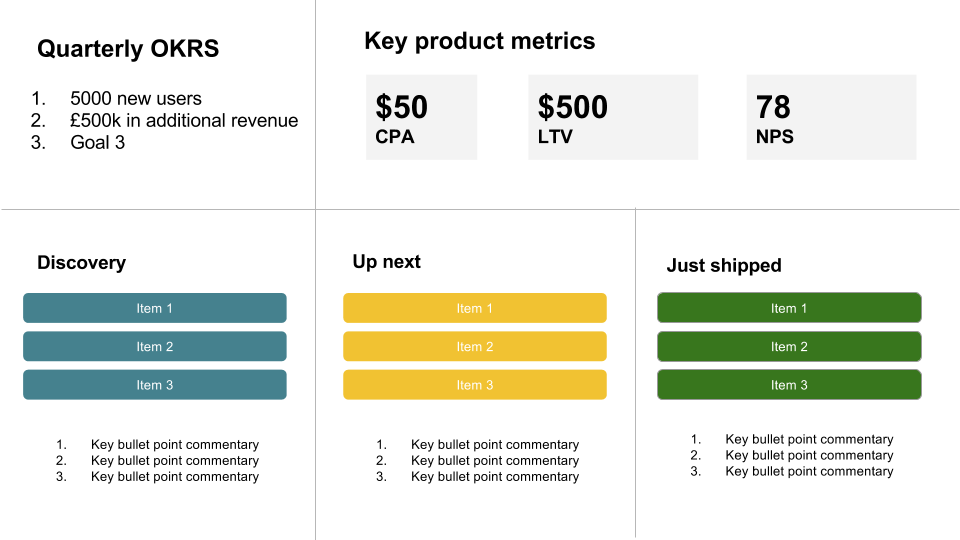

Providing the value proposition of your SAAS business solves a pain in a differentiated way, it’s easy to see why the SAAS subscription business is lucrative. Customer acquisition costs (CPA) and lifetime value (LTV) are the 2 competing metrics that need to be optimised effectively in a SAAS business to keep your monetization mechanism working.

Reducing subscription risks

The greatest risks with subscription models, particularly when introduced as a hard paywall after a growing a user base which is accustomed to free, are that you:

- Frustrate your user base and force them to look elsewhere or

- You are unable to convince them to pay in the first place (high CPA) or

- that you fail to provide enough value to justify the price demanded (low LTV).

Consider carefully which aspects of your product to offer as on a subscription only basis, which segment of your audience to sell this new offering to and how much of your value proposition should remain free.

3. Advertising / commercial partnerships

Commercialising content or products through advertising and commercial partnerships sounds easy. Often, it’s not so simple.

Before you can commercialise anything you need an audience. If you have an audience, advertising to them can risk alienating or outright offending them to the point where they get up and go elsewhere.

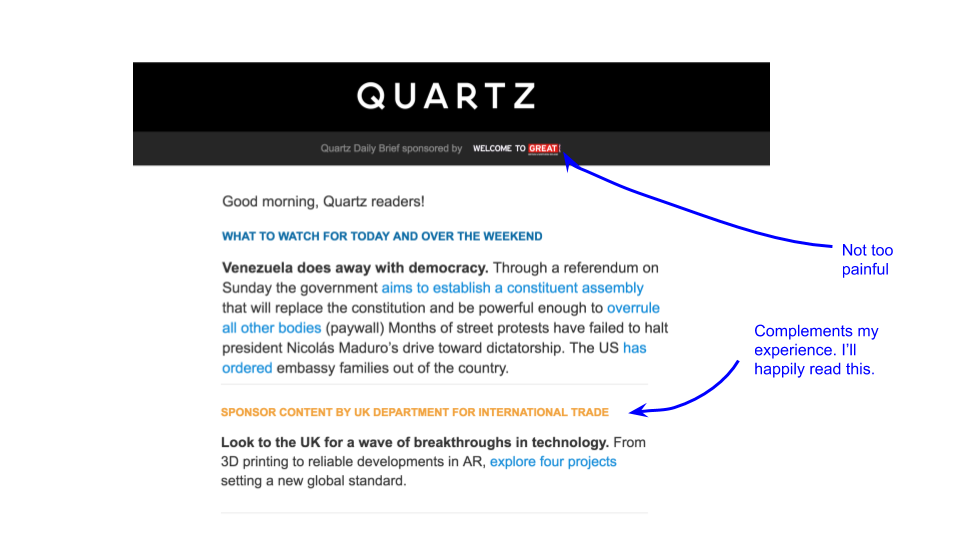

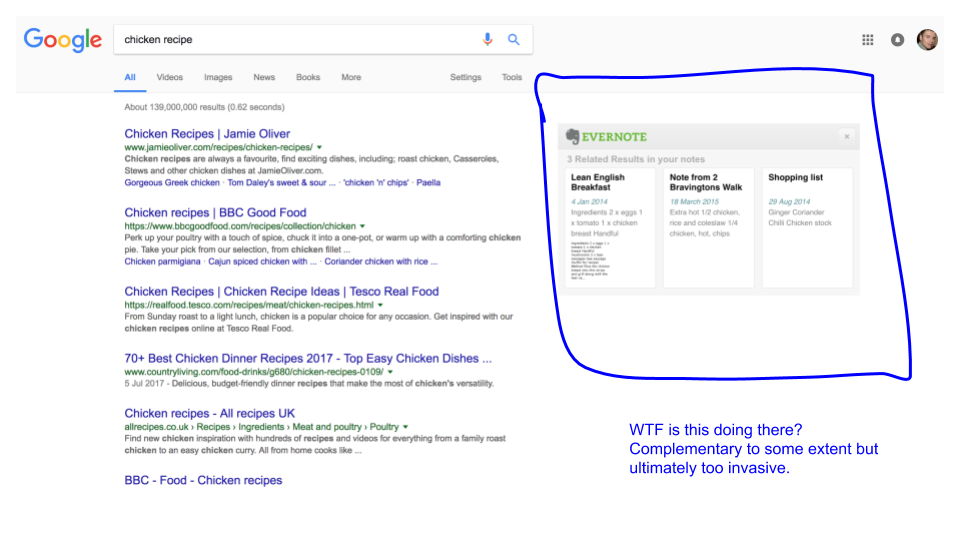

The introduction of commercial content can either complement or compromise the user experience.

Users are largely ambivalent to seeing google ads appear in search results, but these same users will get rightly pissed off when you start polluting their $130 Google Home speakers with the same commercial content. Same content, different context. And a different reaction from your users.

Introducing advertising and commercial activity is a delicate act. There are many factors to consider:

- The context – Is seeing an ad in this context going to cause a disproportionate amount of friction / misery for the user? Google’s controversial email targeted ads didn’t go down well. They felt invasive and intrusive.

- The brands – do you really want any brand to be associated with yours even if they pay you the dollar you need? Consider the implications that associating with another brand will have for yours.

- The messaging – Inappropriate messaging can have a knock on effect – either positive or negative – to your product / business.

- The format – I’ll happily live with the occasional display ad online. What drives me to tears however, is autoplay video ads. The ones with the volume already turned up. I hate them – and I then hate the websites that allow them.

- The volume – 1 minute of ad breaks between episodes when catching up with a TV series through video on demand platforms seems tolerable. Sitting through 5 minutes of ads seems nightmarish.

- The control – I might decide to sit through a 30 second ad break in YouTube. I might not. Giving your users some degree of control over how much commercial content they have access to will make them feel more valued – and more in control.

Depending on the type of product you work on, commercialising specific aspects of your product may be a proven part of your existing model. You may have already proven that your users are happy to have certain aspects of your product offering commercialised.

Introducing new commercial content is where you need to carefully consider the overall experience. Whilst you may spend a lot of time actively avoiding your sales team, working closely with your advertising teams can foster new ideas for monetizing existing and new products.

Advertising as an upselling tactic

Advertising and commercial partnerships can also be used as a tool for upselling / upgrading to paid for, ad-free models of your product.

A certain proportion of your userbase will dislike the commercialised version of your product so much that they’ll pay you to get rid of the ads.

This is a double edged sword: on one hand it means you’re generating new revenue streams (good), on the other hand the revenue is a byproduct of the pain you’re clearly inflicting upon your users through advertising (bad).

4. Bundling and packaging products

You may find that your product suite includes disparate, stand alone products which by themselves don’t amount to enough to generate significant revenues. Bundling and packaging your products together into new, unique offerings can help to generate new revenue streams.

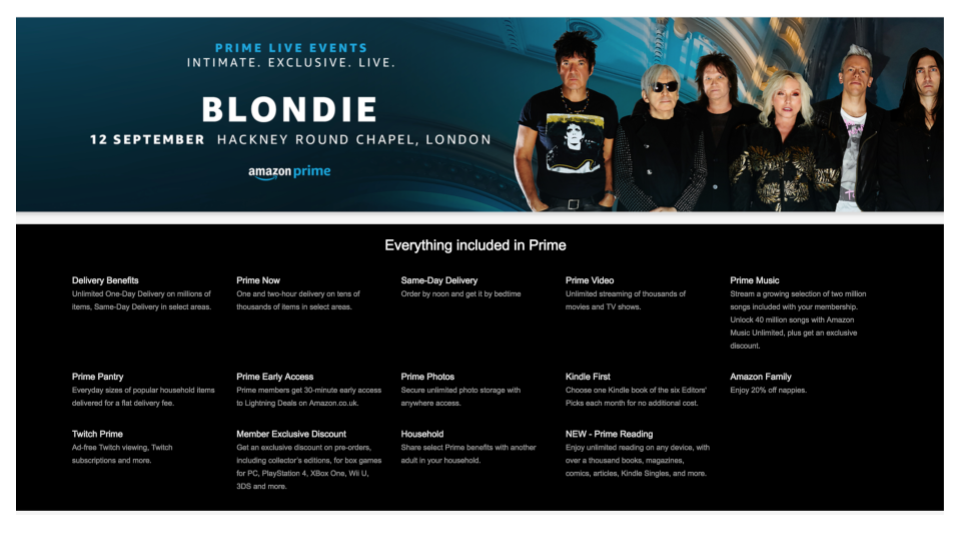

Amazon Prime is a fine example of product bundling. For a nominal fee of $x / month, you’ll not only get the core value – free next day delivery – but you’ll also get:

- Prime Now – one to two hour delivery

- Prime Video – unlimited streaming of thousands of TV shows

- Prime Music

- Prime early access

- Prime photos

- Kindle First

- Twitch prime

- Prime reading

Amazon is king of the bundle.

Look laterally across your business and ask yourself what other under-utilised offerings does your product / business have? Can these seemingly unrelated offerings be creatively bundled together to offer something new or compelling to your audience?

Pricing your bundles attractively can help both you as the seller and your customers as the buyer.

5. Selling services

There’s often a line drawn between products and services and businesses will typically choose between the 2. Historically, a product is a tangible form of value which can be bought and sold and a service is an intangible form of value provided by human beings.

One definition is that a product is typically made then sold whereas a service is typically sold then made.

Software companies are adept are blending the two into 1 offering so that it’s not always clear what the distinction between a product and service actually is.

Either way, looking at what services your product might be able to offer to your existing or future user base is a creative way to generate monetization ideas.

Some examples include:

- Offering a CV clinic service as part of your jobs board website charged at an hourly fee

- Offering a returns label generation service as an upsell for your ecommerce product charged at $X per label

- Offering an add-on cleaning service for a holiday home rental website for additional fees

How to get your organisation to think commercially

Monetization strategies are part of a larger mindset shift towards becoming more commercially savvy.

If you’d like your business or your team to become more commercially savvy you won’t be able to change your organisation’s mindset over night, but there are a few ways to prompt your teams to think more commercially:

- Commercial hack days – Just like your engineering teams are focused on building new stuff in hack days, a commercial hack day can take a similar set up. Ask your teams to come up with 5 new ways to commercialise aspects of your business. Involve everyone – including the engineering teams (they’ll want to kill you) – and see what results you get.

- Cross functional teams / culture – If possible, try to foster a cross functional culture so that your commercial teams work closer with product / technology. If you can’t completely enforce cross functional teams (which isn’t always suited to every company) at the very least make sure you catch up regularly and factor commercial considerations into your roadmap.

- Linking roadmaps to commercial OKRs – When putting together your product roadmap, link some of the features / items on the roadmap to financial / revenue-based goals. Whilst the focus of a PM is first and foremost on delivering value to your users, it’s important to remember that product features will ultimately impact the bottom line, too.

Depending on the nature of your organisation, you may be extremely commercially driven, not commercially driven at all or somewhere in the middle.

Becoming more commercially savvy will allow you to bridge the gulf between your commercial teams and product teams and no – it won’t (always) turn you all into chest thumping, Wolf of Wallstreet wannabes.